Prey is a game I might describe as attempting to be a spiritual successor to System Shock. Some people prefer to liken it to Bioshock, but I disagree. Prey shares more in common with System Shock 2 than anything, with Arkane’s own Dishonored franchise thrown into the mix for good measure.

A similar sci-fi horror setting makes for a superficial resemblance to the games Prey is mimicking, but there are plenty of other little nods. Exposition delivered via audio logs—something that makes little sense in a lot of settings, but works well for titles where scientific research is being conducted. A narrative pieced together from various clues discovered in a relatively open environment. Scavenging for supplies and having to pick your fights carefully.

But while these superficial similarities certainly give Prey the look and feel of Shock, it fails to capture the atmosphere. The feeling of isolation and dread, of something horrendous potentially lurking around every corner, of a truly disturbing villain taunting you at every turn.

Am I looking at this through rose-tinted glasses? Sure. But when people are comparing Prey to both System Shock and Bioshock, it’s entirely fair to compare and contrast the new game with the old, even if I do tend to see the old games with a degree of nostalgia and fondness not present in this new game.

Leaving the comparisons to older games aside, what does Prey bring to the table? A fairly standard opening act involving science experiments gone awry, which makes for a solid, if generic, start. The player is introduced to the concept of the Looking Glass technology – a sophisticated virtual reality style system capable of showing utterly realistic worlds – along with the primary MacGuffin of the game: Neuromods, a revolutionary technology capable of implanting memories, knowledge, and even superhuman powers.

These implants allow for the player to customise and improve their character in a variety of ways, including the usual suspects: extra carry capacity, stat boosts, easier hacking, and so on. But arguably the most interesting are the Typhon abilities, based on the primary enemy you’ll face in the game, an extra-terrestrial menace hell-bent on destruction. Unfortunately, that’s about as involved as the Typhon get.

The Neuromods themselves are administered via jabbing a needle into the eye, pushing this simple plot device more into the territory of horror than the ostensible antagonists of the game ever manage. Add to this the method by which Neuromods are created – which I won’t spoil here – and you have more of a psychological and body horror affair, providing a more effective horror atmosphere than the enemies you’ll fight at every turn.

Unfortunately, Prey suffers from the lack of a truly satisfying bad guy, like SHODAN, one of the most malevolently interesting and disturbing villains I’ve ever had the pleasure of being pitted against in a game.

Alex Yu is ostensibly the antagonist, at least from the point of view of a new player seeing how he treats his brother/sister, and how he speaks to you during the brief chats you engage in via the station’s communication system, TranScribe. And sure, he’s unpleasant and goes out of his way to make you dislike him, but he’s not exactly a threat.

More than this, the Typhon themselves aren’t all that scary or interesting. They provide for an occasional jump scare if you happen to be exploring and one catches you unawares, but beyond that they’re little more than generic, formless blobs designed to fill a quota for gameplay enemy purposes rather narrative.

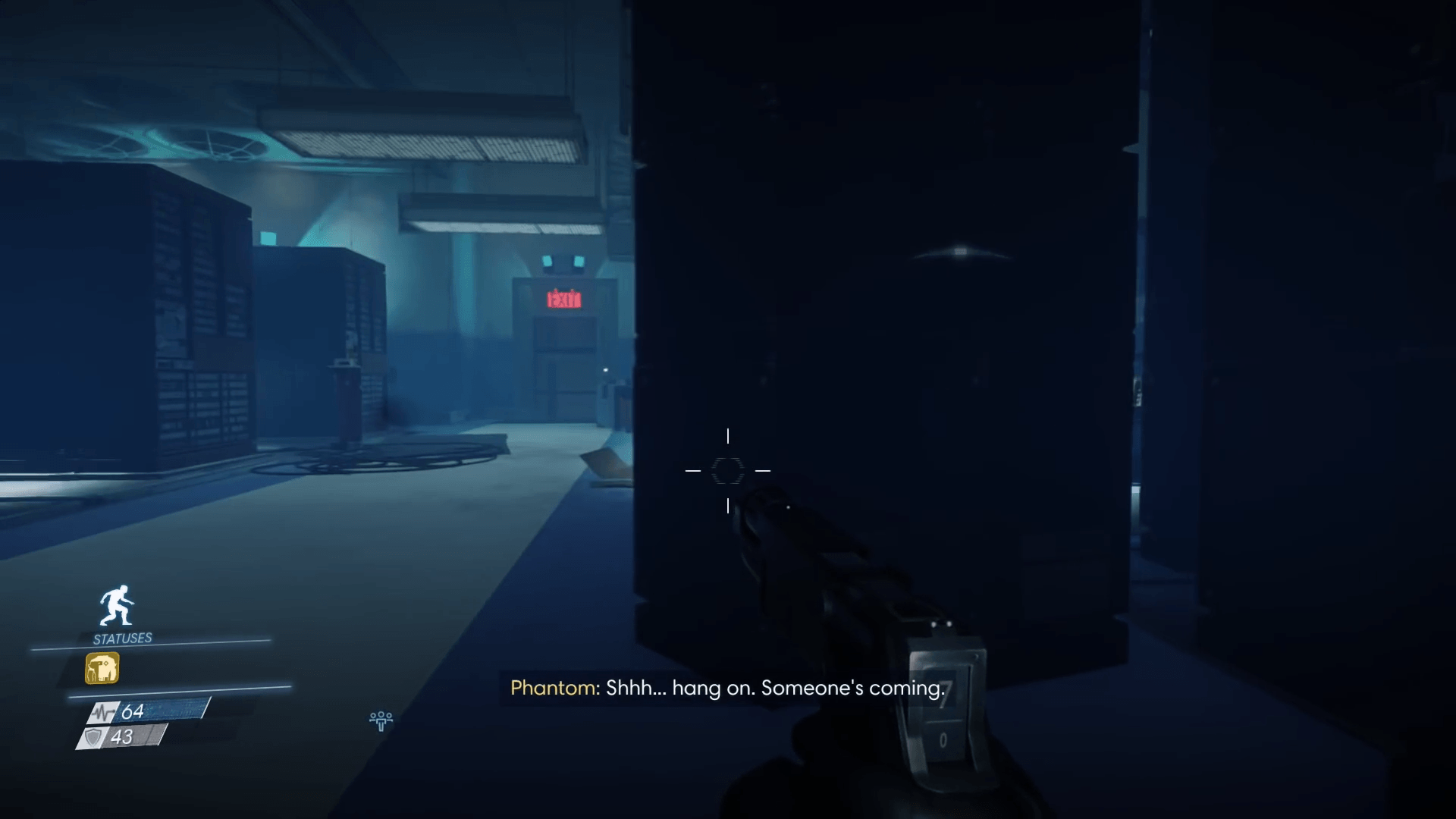

The idea of the Typhon repeating the last thing a victim said is a nice one, if a little uninspired. It gives a similarly creepy vibe to a season 4 episode of Doctor Who called Silence in the Library (Part 1)/Forest of the Dead (Part 2). In this episode, people were being killed by a microscopic organism with flesh eating tendencies, and thanks to the space suits the characters were wearing, an echo of their personality was trapped in the suit’s communication system for a time after death. It was creepy and unsettling, and Prey’s Typhon evoke a similar reaction. It’s just a shame it isn’t explored or capitalised upon as well as it could’ve been.

Prey does a better job with its mystery aspects, giving you regular titbits of information from Alex or other characters that make you question exactly who to trust. And the idea of using a form of amnesia resulting from Neuromod removal gives a solid in-universe reason for the player character being as clueless as the player.

The GLOO cannon is by far and away the most interesting aspect of Prey’s list of gameplay features. At its most basic, this tool-cum-weapon allows you to create makeshift bridges out of blobs of solidified glue, providing a host of opportunities to sequence break, find hidden nooks and crannies filled with delicious loot, and even bypass areas by stopping flaming gas leaks and similar environmental hazards using a judiciously placed blob of goo.

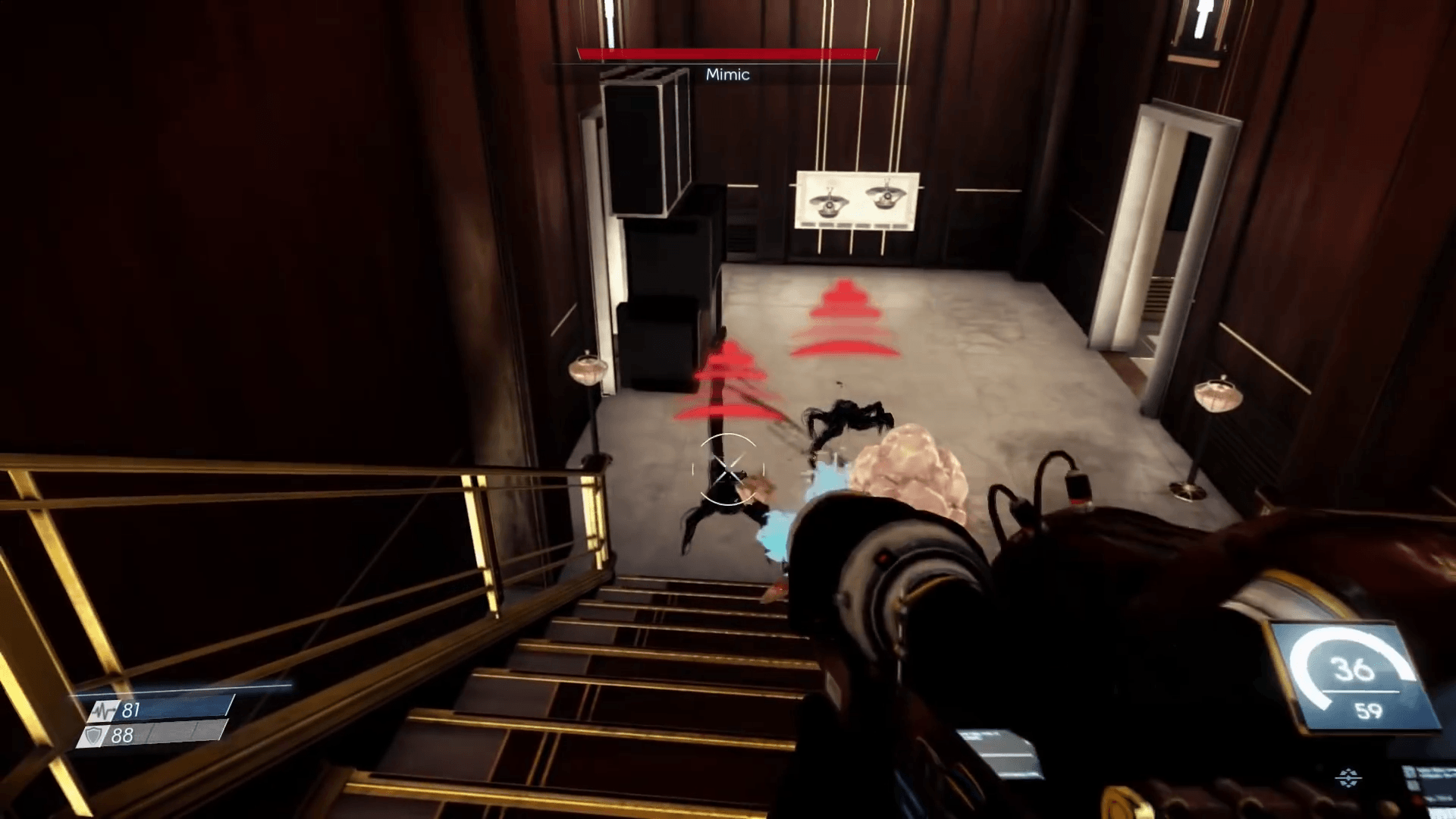

It’s during combat that the GLOO Cannon truly shines, however. While it’s perfectly possible to bash enemies with your wrench, especially the smallest and weakest enemy type, the Mimic, you’ll be doing much less damage than you could be. This is where the GLOO Cannon comes in.

By gluing an enemy, you slow its movement and, with enough shots, freeze it entirely for a few brief moments. This allows you to get in close and smack it with your wrench, or fire a few shots from your pistol or shotgun, causing massive bonus damage. For the more powerful enemies, this is all but required if you don’t want to be seeing the No Life Signs screen.

Additionally, the game has a functional stealth system similar in general use to those of Arkane’s own Dishonored, or Bethesda’s Fallout and Skyrim. Crouch and you’ll be harder to detect. Land a silenced shot on an enemy while hidden and you’ll receive a sneak attack critical, again providing bonus damage. Nothing too special, but it does the job.

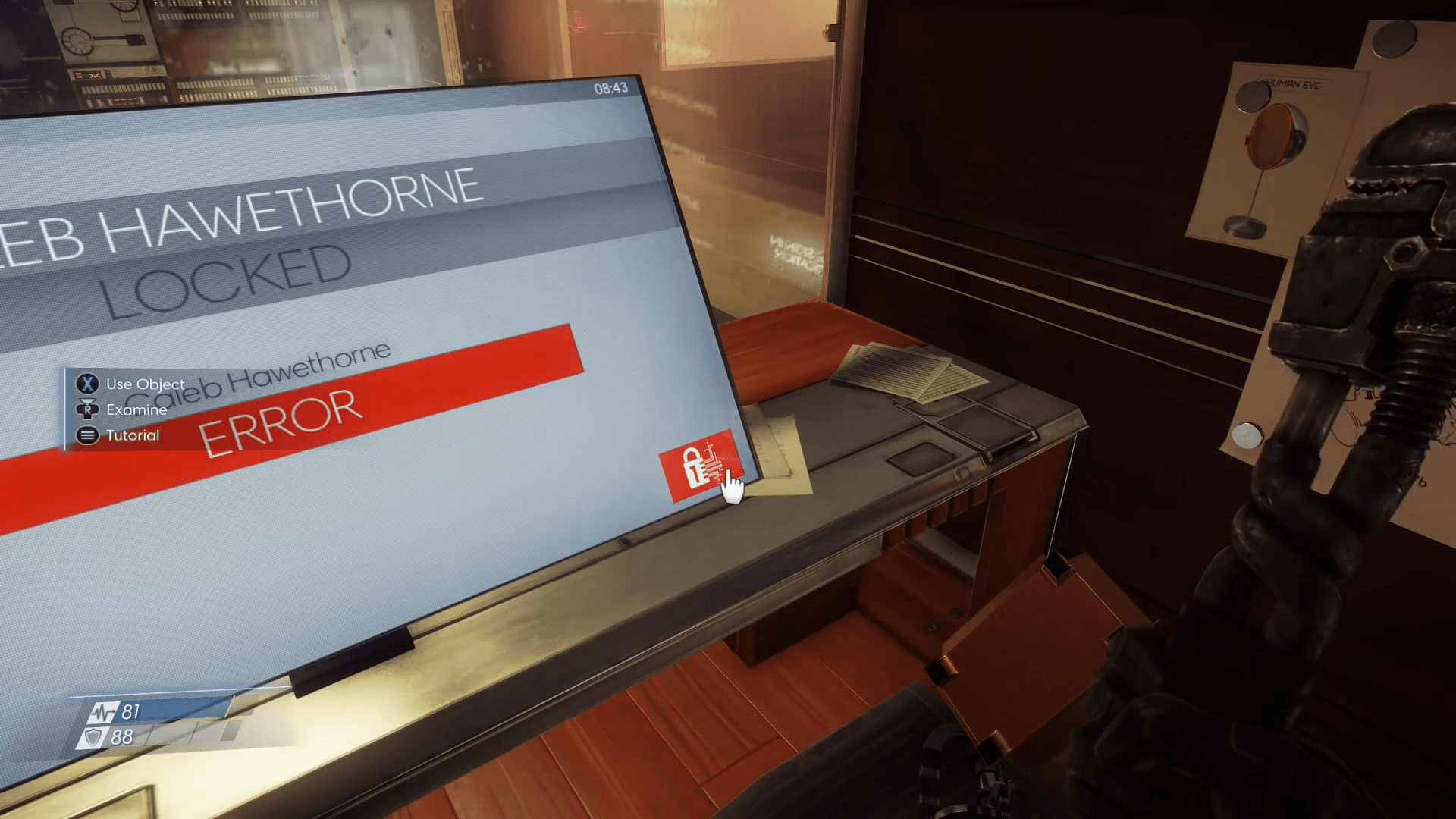

Prey also delivers an impressively open world to explore. Not open as in a sandbox world, but open as in free to tackle quests and exploration in any order you like, provided you’ve specced your character for it. A blocked passage might be bypassed by using hacking on a door elsewhere, or you could use the Leverage skill to physically move the blockage, or a Recycler Charge to destroy the blockage, or even wait until you find an appropriate keycard later in the game and come back to previously locked areas.

The existence of multiple identical fabrication plans – used for the game’s robust crafting system – further reinforce the idea that you’re free to complete the game your way. You might find the plan for shotgun ammo in one location, but in a subsequent play-through, your differently-specced character can’t get into the same place, and instead finds the shotgun ammo plan in a wholly different area. Rarely are you locked out entirely, but you will need to explore thoroughly to find them.

This freedom comes with a potential downside, though, in that you can feasibly create a character who literally can’t progress. By speccing into specific skills and not focusing on combat skills enough – whether physical weapons or the Typhon abilities – it’s possible to create a character who can’t deal with obstacles later in the game.

A game that doesn’t unnecessarily hold your hand and that is willing to let you fail is normally a good thing. I like my games to have meaningful consequences, and being able to create a broken build is something I appreciate. But not everyone has the time or inclination to roll a new character after 12 hours because they made a few poor – or more accurately, uninformed – decisions early on.

The game’s balance could also do with some work. Early game tends to be a scavenger hunt for supplies while avoiding enemies or using sneak attacks for bonus damage. But by the time you hit late game, you’ll most likely be swimming in Neuromods and ammo, removing some of the challenge. On the other hand, enemies do keep scaling in difficulty, with a reasonable variety of types (elementals, telepaths, etc.) to keep players on their toes, so it really comes down to player skill and character build as to whether you’ll struggle or not.

Turrets can be a huge help not only in the early game, but right up to the end, even if it’s only as a distraction tactic. Judicious placement of a few turrets can easily turn the tide in your favour, but likewise, if you spec into the Typhon abilities, turrets will turn on you, considering you to be an enemy as a result of your Typhon Neuromods. It’s a fun little consequence for going down the less than human route, and doesn’t feel quite as shallow as the Adam choice in Bioshock.

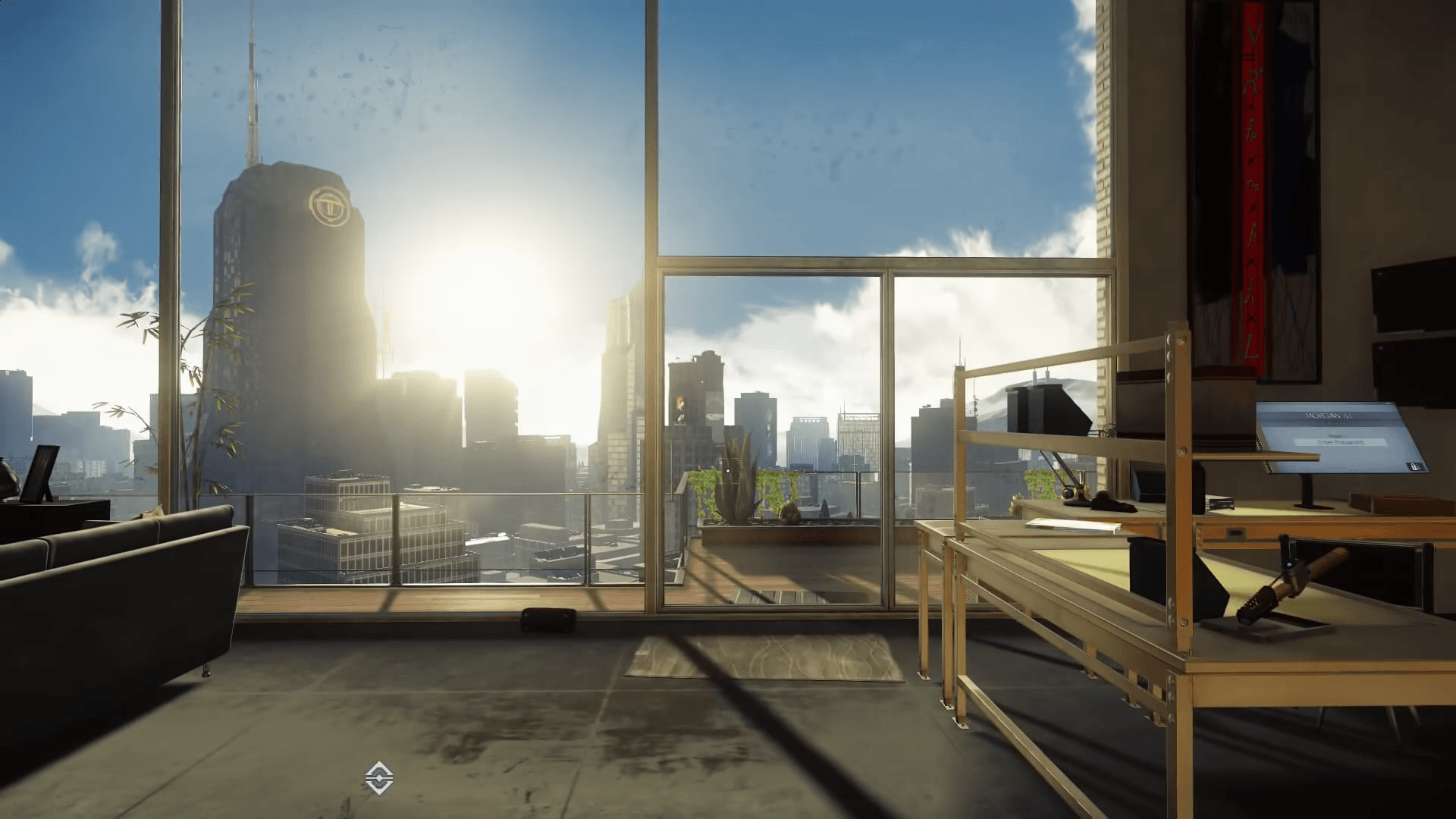

Prey has the by-now familiar art style of Arkane Studios, with its cartoony characters and vivid colour palette, providing a beautiful backdrop against which to place the ugliness of death and human fragility.

Performance is rock solid for the most part, easily on equal footing with the other successful release published by Bethesda in recent memory, DOOM. You should find smooth framerates and no hitching or other hiccups here. However, the game does have a few bugs, one of which is utterly game breaking if you don’t happen to know how to fix it.

Overall, Prey has decent sound design as well, insofar as the ambience and music go, and weapons generally feel both weighty and fun to use. But then you get to the voices. The main characters are fine, no issues there. But the balance of background characters such as the Operators is completely out of whack, with random incidental sounds such as a greeting overriding the character you’re currently speaking to directly.

In conclusion, if you’re an exploration nut, or you’re in it primarily for the gameplay, Prey will more than deliver. But if you’re in it because you loved System Shock 2 and are looking for another experience akin to that, at least as far as narrative and mystery are concerned? Prey might do little more than frustrate you, or it could scratch that itch. And if this is your first rodeo with this type of game? It could potentially be your game of the year.

The gaming landscape is different now. Gone are the days of hardcore experiences like System Shock 2, at least in the AAA space. The massive success of games such as Fallout 3 and Skyrim brought millions of new gamers into the fold, boosting video gaming even further into the mainstream. And with mainstream success comes what I like to call the Hollywood Effect: streamlining, casualization, and appealing to the masses in order to maximise profits.

And while Prey is a shining example of AAA gaming done right, it doesn’t quite live up to the game I consider it to be a spiritual successor to. But that’s okay. Prey succeeds on its own merits and gives me hope that AAA can still produce excellent quality titles, full of open-ended gameplay and creativity, albeit with some generic ideas that don’t really do anything new.

This post didnt have a specific author and was published by PS4 Home.